Now that the last American soldier has left Afghanistan and the evacuation is complete, the news media is dropping its focus on Afghanistan. But we ourselves must not look away. We must learn everything we can about what happened – and why. We must learn what we need to know to avoid such a catastrophe ever happening again.

As it is, even now, the House Armed Services committee just endorsed a Republican plan for a $24B amendment to the defense budget. So no one should delude themselves that our exit from Afghanistan has slowed down the pace of the US war machine. For the citizens of Afghanistan, everything changed in an instant. For the military industrial complex, very little has changed at all.

It is incumbent on us, as citizens, to ask how our war councils operate – both our military and our civilian leadership. Clearly, given the last twenty years of ultimately futile war in Afghanistan, we have every good reason to ask that question. In fact, it is irresponsible for us not to ask. There should be an official Commission established to determine why it is we failed so miserably in Afghanistan, at the cost of so much blood and treasure. Yet you and I know that there will not be.

That’s why we, as citizens, must do the work that our government will probably refuse to do: look back, and try to understand.

I understand why we went into Afghanistan, and I also understand why we initially remained. You can’t just topple a government and say, “OK guys, now we’re leaving.” We did have a responsibility to the Afghan people at that point. Reasonable people could have seen a short, strictly limited mission in which we seriously tried to help the country rebuild before we left.

But that is not what happened, as we’re all now glaringly aware. We stayed for twenty years to fight a war in which it appears we did far more harm than good, laying bare the ugliest shadows of American militarism, hubris and hypocrisy. We neither understood the people of Afghanistan nor showed respect to their culture, installing and enabling a government that was almost as abusive to them as had been the Taliban. We did not export democracy to Afghanistan. While we waged war, we made no effort to wage peace – displaying a tragically obsolete mindset that exalts the use of brute force over every other problem-solving option.

It’s not okay to say “Well it’s over now. That’s good!” and then just wash our hands of it. We owe it to every American and every Afghan who died in that war to make sure they did not die in vain. We must learn from this – we must understand what happened – or we will repeat this tragedy in the years ahead just like Afghanistan was in far too many ways a repeat of Vietnam.

I will be posting several interviews with people who can illuminate our understanding. Some of what you hear will infuriate you, and some of it will bring tears to your eyes. But I’m committed to understanding as much as possible so as to be a conscious citizen going forward. And I’m sure you are as well.

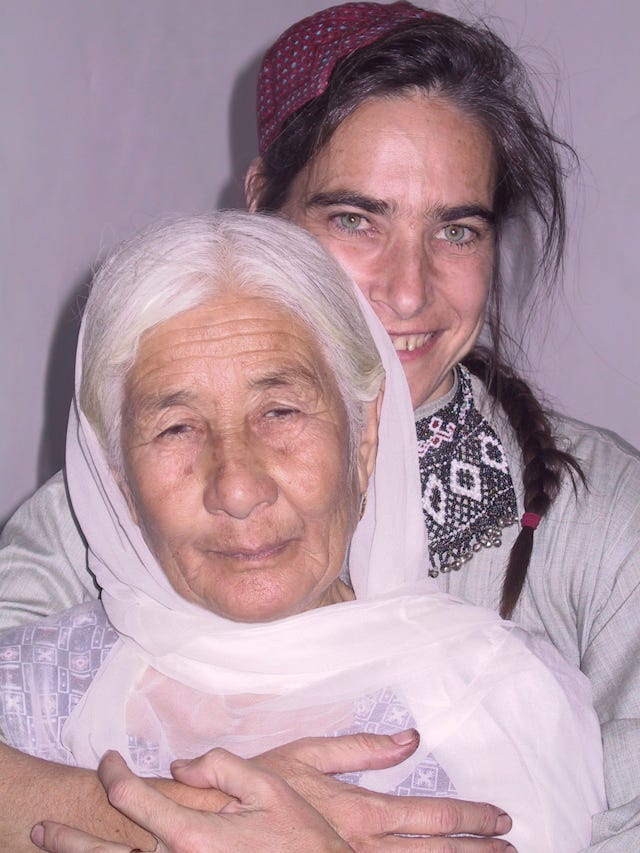

The series of interviews is called Reflections on Afghanistan, and this first one is my interview with Sarah Chayes, a former NPR reporter and special advisor to former head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mike Mullen. Sarah wrote the article The Ides of August, and I suggest you read the article before watching the interview. It will make it even more edifying.

The war is over but the pain is not. My deepest prayer is that it be a pain that changes us.

Excerpts from the interview:

Marianne Williamson:

Sarah, thank you so much. I am so grateful to you for being here.

Sarah Chayes:

I am delighted to be with you for this conversation, Marianne.

Marianne Williamson:

Thank you. I want to read to you a little bit from your article:

“Americans like to think of ourselves as having valiantly tried to bring democracy to Afghanistan. Afghans, so the narrative goes, just weren’t ready for it, or didn’t care enough about democracy to bother defending it. Or, we’ll repeat the cliché that Afghans have always rejected foreign intervention. We’re just the latest in a long line. I was there. Afghans did not reject us. They looked to us as exemplars of democracy and the rule of law. They thought that’s what we stood for.

“And what did we stand for? What flourished on our watch? Cronyism, rampant corruption, a Ponzi scheme disguised as a banking system, designed by US finance specialists during the very years that other US finance specialists were incubating the crash of 2008, a government system where billionaires get to write the rules. Is that American democracy? Well..?”

According to you, when we went into Afghanistan, it was not necessarily seen as an invasion. We got rid of the Taliban, and the Afghani people were open to what might happen. But what happened after that?

Sarah Chayes:

Like, there was a window of opportunity to help build something that could hold, and that could be responsive to the aspirations of the Afghan people. And we were not doing that, so when I hear, “We shouldn’t have done nation-building,” I kind of say, “Well, what nation-building did we actually do?”

The second thing I’d like to say is you can’t just topple a government and then walk away. I mean, you know, even when we go to buy something, right? Fragile and breakable. You know the expression, “You broke it, you own it”? Well, I mean, I just don’t quite understand what that would have meant, to walk into Afghanistan, topple the government, and then dust our hands off and walk away. What do we suppose would have happened?

Marianne Williamson:

What you make clear is that the corruption of the Afghan government was an abuse that was almost as bad in the lives of the Afghan people as was the abuse that they suffered at the hands of the Taliban. Please explain that to us.

Sarah Chayes:

Well exactly, and what I really appreciate in what you just said, Marianne, is that you’re making a distinction between a sort of reductive, on-off idea of what a decision is. “Do we go or do we stay?” You, in your question, just got below that, and you said, “If we stay, how do we stay?” And that really matters. How do you stay, if you choose to stay? How do you go, once you’ve decided to leave? And in both cases, I think we did the how very, very badly. And I started seeing, early on-in the summer of 2002 – I remember getting a group of young people together, because we wanted to launch this radio station, and the idea was, you know, “What do people want to listen to?” This was going to be certainly the first independent post-Taliban radio station, maybe the first independent radio station ever in Afghanistan. And the kids were… They kept talking about security, but they didn’t mean security against the Taliban. They meant security for people against the militias, who were roaming around, that we, the United States, had armed, that we had dressed in US Army uniforms, that were loyal to a man who had imposed himself as governor, in fact against President Karzai’s wishes at the time, and were, you know, treating people very badly.

And I had half a dozen specific stories like that, and these people were dressed in US Army uniforms. So what were Afghans to think, other than this must have been how we wanted things to go?

And very quickly, I was started making this point, that what is really going to matter here is how the Afghan government treats its own people. And unfortunately, you mentioned the CIA, and what they had done was kind of connect with the warlords, whom the Taliban had kicked out of the country back in 1994. These were people who were responsible for a kind of chaotic, violent, extortionate mayhem during the late… I would say during the very early 1990s, after the Soviet Union pulled out.

The one thing that Afghans were grateful to the Taliban for was kicking these people out of the country. Everyone I talked to said that. They detested the Taliban, but at least they got rid of the warlord. So what did we do? We allied with those very same warlords, and brought them back into the country, and put them in position as governors of the major provinces. It was almost as though you had a cancer patient, and you had gotten the patient into remission, and then you take a syringe full of cancer cells, and you inject them back into the body of the patient.

Marianne Williamson:

Did the CIA, did intelligence, so-called intelligence, not know what you were just saying, that the warlords were actually as bad, in some cases worse, to people than the Taliban were, and that we were putting our trust and giving our support to people who were negative, abusive, corrupt influences in the lives of people? Did we not know that? You make it clear, in things that you’ve written and other interviews that you’ve done, that during the Obama administration, you certainly tried to tell them.

You say that among the high-level Obama administration people, you argued, what’s the point of doing all this military action if the government is so corrupt that people will hate its own government, and how do you expect them to want to stand up against the Taliban? You have said in other interviews that Mike Mullen heard that, but that Mike Mullen, because he was joint chiefs of staff, he was the military, this was really not under his control. This had more to do with State and presidential decision-making, which of course means Hillary Clinton.

Marianne Williamson:

Now let’s talk about Karzai. He was our guy. That’s why the US backed up, but you yourself were gobsmacked when you first realized that Karzai – who was America’s chosen guy to run this government, which in fact was a corrupt government anyway – had actually been one of the people who brought the Taliban to Afghanistan originally. According to your reporting, the Taliban did not emerge almost spontaneously from Kandahar the way we have been told, but they were actually a product of Pakistani military intelligence working with Karzai. And that during the 1990s, Karzai was actually representing the Taliban or was going to represent them at the United Nations. Certainly, the United States knew we were in a war with the Taliban, but that the person we had chosen to head things for us in Afghanistan had helped create the Taliban.

I don’t think the American people knew this. It is very obvious that the corporate mainstream media was doing nothing other than parroting whatever the White House was saying. I think we are looking to people like yourself right now, because we have to do the investigation ourselves.

Sarah Chayes:

(There were some very good reporters on the ground, but they often had trouble getting their stories even printed. Also, more people get their news from television today. )

And I’d also like to say, military officers on the ground … I mean, I have a lot of respect for the ones that I met. The people I really hold to account here are the senior leaders on the civilian side for the failure to address the two major political and diplomatic issues, which were, as you pointed out, Pakistan and corruption, and senior military leaders for this. What were we doing creating a conventional army in Afghanistan with people who knew how to fight a guerrilla war and were fighting against guerrillas? Why did we turn them into a conventional army that was bound to be completely dependent on expensive material and American trainers and maintenance, people, and things like that? And there we get to the corporate point that you made, which is to say …

Marianne Williamson:

And you pointed out that there was so much money to be made doing it that way, because of all the material that would have to be bought from American defense contractors. If they really wanted to be preparing an army, they would have been preparing an Afghan army, not an army that’s merely an extension of our own. The hubris of the Americans. The arrogance of trying to remake Afghanistan in our image. So we made it as corrupt as we are at this point.

Sarah Chayes:

I would say we tried to remake Afghanistan in, frankly, the image of what we thought Afghan society was, which is violent warlords, that kind of thing. We never really made an effort to bring our ideals of democracy and rule of law to Afghanistan. There was never any effort to bring that. And as you beautifully said, what we did was kind of unwittingly or almost-we exported the version of the American government system that we are currently experiencing. And that is where I see Afghanistan as a very sobering mirror that is being held up to us today. If we don’t understand how Afghanistan is a reflection of us, we might be in for scenes like the ones we’ve been seeing in Kabul airport. That’s my concern.

Marianne Williamson:

Robert McNamara famously said, “We didn’t understand the Vietnamese people. We didn’t know their religion. We didn’t know their history. We didn’t know their culture and we didn’t have anyone to teach us.” It seems to me that to be the same disconnection between the war planners in the Afghan war. As in Vietnam, you don’t know anything about these people and you’re not even trying to find out.

Sarah Chayes:

And instead of trying to find out, what we did was presume certain stereotypes. So I received recently a comment to my post, The Ides of August from a retired military person who said, “Well, here’s what I used to tell my soldiers, ‘Check your American values at the door. Corruption is just part of Afghan culture. Don’t even think about corruption.” So what I wrote back to him was, “Could you please tell me where you got that information? Which Afghans informed you that they enjoy being shaken down abusively and contemptuously by their own government officials?” That’s all I wrote.

Marianne Williamson:

Tell me more about Pakistan.

Sarah Chayes:

The Pakistani government was arming and training the resurgent band and the United States government was providing the Pakistani government with a billion dollars a year in military assistance.

We kept saying, Pakistan has to “do more to stop the Taliban.” And I said, what are you talking about? They’re actually constituting them. They aren’t retraining them. They’re equipping them. And indeed, they are providing them with plans.

Marianne Williamson:

There’s no way the CIA didn’t know this, isn’t that correct?

Sarah Chayes:

That is my personal view. Because they could see it. They could see what Pakistan was up to, in particular officers who were stationed up on the borders, the Eastern border, because they were being shot at. And they could see not only what country it was coming from, but when it was coming from Pakistani military bases, that they were being shot at from inside the perimeter, the bases on the border. And so, that is why the military began slowly to come around on Pakistan.

Marianne Williamson:

You felt that Biden understood that as well.

Sarah Chayes:

Not from direct interaction with him, but there was a story that went back, I think to 2009, which is… or late 2008, but he traveled to Kabul and had dinner with President Karzai and was so displeased by what he was hearing, that he actually stood up and walked out of that dinner. And he was the only person raising the issue of corruption within the Obama administration.

That being said, my impression is that he was also somewhat reductive in what he thought the answer then was. And it was, we got to get out of there. And again, back to how you began this conversation, it’s the how as well as the what, and my sense was that his office was not particularly concerned with the how. Argued strongly against a troop buildup, which I think was a perfectly fair position.

I just wished that we had had a governance buildup. I wish that we had thought we had realized that maybe it’s at least as difficult, if not more difficult to run an Afghan city than it is to command a company or a platoon of Afghan soldiers. Why did we not have mentors with civilian officials? And so in 2009, in January of 2009, I actually wrote up a sort of comprehensive action plan for Afghanistan. It’s about eight pages long. It’s also on my site, Sarahchaise.org. And at that time, I was in contact with incoming members of the Obama administration. I provided that plan to Richard Holbrooke, who was going to be tapped to be the Special Envoy and to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton herself, because I was invited to her first dinner at the State Department with a number of Afghanistan and Pakistan folks.

And I also provided it to senior military officers. So what I’m trying to say here, I’m not saying that my plan was the be all and end all of what we ought to have done, but it was a significantly different approach that was possible to implement and that we did not implement. And so again, if then Vice President Biden had been concerned about corruption, did he have thoughts about how we might address that? I didn’t see any evidence of Vice President Biden wading in to say in that case, alongside the troops that we’re sending in, we need to do this, that, and the other thing to address the problem of corruption. That I never saw coming out of his office.

Marianne Williamson:

Even if he had complained, who knows what difference that might have made. And he said in one of his speeches recently, he’s been to Afghanistan four times. He knows how corrupt it was.

But in any relationship, it is as important how you leave as how you stay. Talk to me about the exit. In your opinion, did it have to be this disastrous? Many people say, “Look, losing a war is messy, getting out is messy.” I appreciated it when I heard you say there’s something very unseemly about just writing it off as “messy,” given how many thousands of people’s lives are so horribly affected by it. Could this have been done in a way that would have been much better? I would assume that you’d say it was done the same way we did everything else regarding Afghanistan: with very little concern for the people who were living there.

Sarah Chayes:

That’s exactly how I feel about it.

Marianne Williamson:

I had heard you say in another interview that it seemed to you that President Biden basically just had a on off switch about Afghanistan.

Sarah Chayes:

That is my feeling. And what I would say is that the Doha negotiations that took place, particularly in President Trump’s administration were absolutely devastating to the Afghan government. Concession after concession was wrung out of the Afghan government in order to make it possible for us to say that we were withdrawing with a peace treaty with the Taliban. I mean, it was just when the Afghan government was not even at the negotiating table. Yeah?

Marianne Williamson:

Not only that, but then Biden keeps saying, oh, I just inherited this bad deal. He could have changed that deal.

Sarah Chayes:

That’s exactly where I was going with that. Marianne, thank you for saying that. In other words, why President Biden’s say, wow, among the other messes I inherited from my predecessor and I basically… He reversed the departure from the Paris Climate Accord. This wasn’t a treaty and he could have said, you know what? This person, my predecessor negotiated a settlement that was completely unfair to our allies in the Afghan government, our nominal allies, whatever. And he could have removed the individual who negotiated that deal, that was so beneficial to the Taliban and so detrimental to the Afghan government.

Marianne:

I appreciate that we didn’t belong there, but the way we exited…

Sarah Chayes:

Right. Or we didn’t belong there the way we were there is what I would say.

Marianne Williamson:

And what now?

Sarah Chayes:

This is not the Afghanistan of 2001, that there’s a whole new generation of Afghans. We’ve been hearing that a lot. The same thing goes for the Taliban. This is not the same Taliban as the 1990s. This is a Taliban that has been watching from the sideline as people they know have been getting fabulously rich on the kind of international development Mana and not to mention also the drug trade. Right? And so, the Taliban are very interested in tapping into some of that.

And that helps explain why we’ve been hearing these mollifying statements and pronouncements from Taliban officials, because those ones are anxious to gain some kind of international credibility and recognition and whatnot so that they can tap into luxurious meetings in Doha and then Europe and in the United States and development money and whatnot. There is a faction that is much more hard-line and the fighters, I think the field commanders who didn’t enjoy that type of diplomatic luxury, they from what I am hearing are not so wild about these outward facing pronouncements. And that may explain why we don’t see a new president of Afghanistan yet.

Marianne Williamson:

I’d like to ask you about the women.

Sarah Chayes:

I think that the women who might be in a position to resist a “return” to those conditions will be women. I do not foresee a mass slaughter of women. I wouldn’t put it past the Taliban to commit some exemplary, gruesome assassinations of women who have been in the public eye, but they’re not going to go door-to-door and drag women out of the houses. They can’t afford… Religiously, they can’t do that.

The situation for women is going to be grim. And all I can say is that I hope this generation of women that has, in some of these major cities, been able to step forward, I hope that they take a deep breath, connect with each other, and start thinking about what kind of Afghanistan they live in, and begin slowly planning for how to bring that Afghanistan into existence with each other, and with men that they trust, because I’m already hearing these Taliban begging civil servants to stay in their positions.

In the last two days, I’ve heard those two publicly calling for Afghans to stay in their positions in government, and for the international community to stay engaged with the Taliban government, because you know what? These Taliban are not capable of governing.

And I think that Afghans need to take a breath and think about how to birth the Afghanistan they always wanted.

And let’s pull back from the specifics of Afghanistan for a moment, and just return to what I was saying about Afghanistan being a mirror of us.

Let’s take a look at the mushrooming growths of McMansions that now encircle Washington, DC. Let’s take a look at the portfolios, the offshore bank accounts, the assets, the pay packages of top executives in, for example, defense contracting firms, pharmaceutical firms, financial investment firms, real estate giants, and the lawyers and brokers that serviced them. Now, let’s take a look at the policies that many of these executives have either influenced because of their connections with top government officials, or have promulgated because many of them have actually rotated in and out of government themselves. Those policies include two lost wars, a financial meltdown that almost brought down the world economy, a global pandemic, and an opioid crisis that both have killed hundreds of thousands of Americans. And I’m sure we could come up with a few others. What I want to know is, first of all, have any of those individuals been held accountable for the abject failure of their policies? And secondly, does this not resemble the developing world fragile and failing states that I’m talking about? There is a network of top business executives and government officials, who often trade places, that really has been in charge in the United States for the last number of decades. And they have promulgated a lot of spectacularly unsuccessful policies. I mean, embarrassingly disastrous policies, while they have been extraordinarily successful in enriching themselves.

This is the mirror that we need to look in. And that’s what I wish more Americans were doing right now.

Marianne Williamson:

Well, I think more Americans are saying exactly what you’re saying. And of course, this refers to your book, On Corruption in America.

And you’re making such an excellent point, that the Afghan war is just an example of the way America operates these days, where money to be made for small group of people takes precedence over the health, and safety, and the welfare, and the security of the American people, other people in the world, and the planet on which we live. I think more and more people are waking up to this. The week before, this debacle in Afghanistan exploded the way it did. We had the UN climate report.

Sarah Chayes:

For sure. And thank you for bringing up the environment because that was the main group that I left out.

I frankly think we have overblown the danger of terrorism from the beginning. I’m not saying that 9/11 was not horrific, but I just think that in comparison with the damage that has been caused by, as you said, by these money-maximizers, compared to the damage done to our health, to the health of the planet, and to our lives, as many people committed suicide in the wake of the crash of 2008, as were killed in the terrorist attacks of 9/11. I actually think that terrorism has been a distraction from the real issues that we need to be focusing on as a nation and as people.

Marianne Williamson:

Thank you, Sarah Chayes. Thank you for putting it out there. And I hope that we will have more opportunities in the future to talk, about things that all of us need to hear. Thank you so much.

Sarah Chayes:

I really appreciate you for having me and for the depth and thoughtfulness of your questions.

Marianne Williamson:

Thank you.